Monet and Venice at the Brooklyn Museum

I’m late, and I’m running.

Holding my coat tightly around me, I rush into the Brooklyn Museum. I’d assumed “Art History Happy Hour” meant cocktails and mingling, so I got cute (thus why I was late). Instead, I found myself quietly slipping into the back of a proper four-part lecture—PowerPoints up, all chairs facing the front! So, a touch embarrassed at being late, I put on my learning cap and waited for the halfway break to grab a drink and a cannoli (always read the event details, people).

The curator explained the difficult logistics of assembling such a loan-heavy exhibition focused on both Monet and Venice as a city. A contemporary conceptual artist broke down how Monet’s radical approach to color and light still shapes his work today. I learned the museum even has a composer-in-residence who traveled with the curator to Venice to record the city’s soundscape—the same city Monet and his wife lived in for two months at the end of the 1800s, despite Monet famously not wanting to go at all. Lastly, we heard from an organization working to preserve Venice as it slowly erodes back into the sea.

So, no—it was not a jazzy little happy hour. But it was smart, communal, and slightly buzzed, which is my favorite way to take in a PowerPoint.

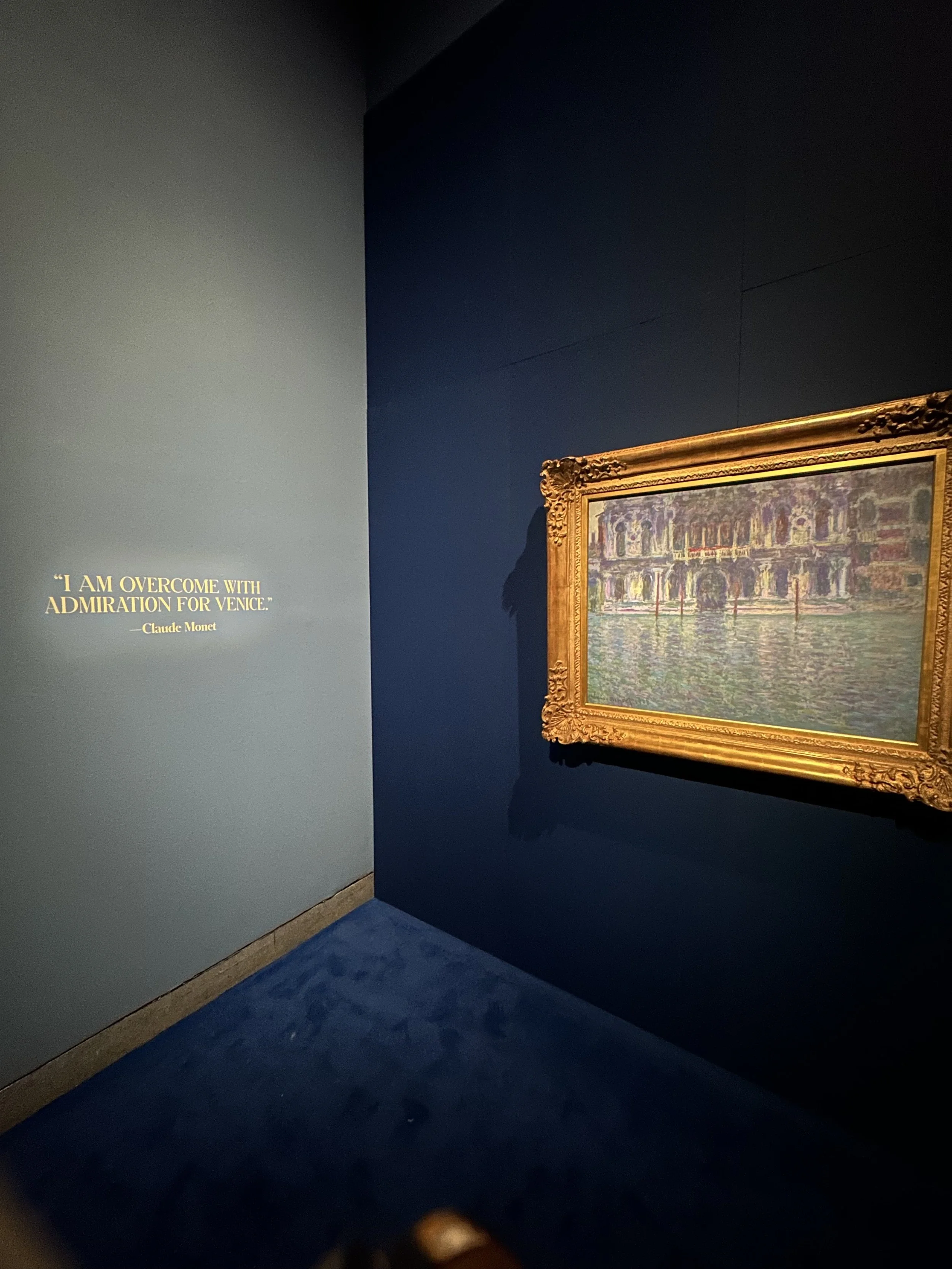

Next, we moved to the exhibition hall for Monet & Venice. It begins quietly with a few photos, an introduction, and then a darkened room filled with a galaxy of screens. Modern Venice fills our eyes and ears—church bells ringing in the salty air of dawn, gulls calling from the tops of Gothic buildings, water slapping stone along the canals, motorboats humming with people on their way to work. Beneath it all is Niles Luther’s composition inspired by the enveloping atmospheric haze Monet chased with near-religious obsession. Having been to Venice myself, I felt like I was there instantly: the hot golden light illuminating the narrow alleyways, water splashing against the steps as we climb into a boat, a gull pausing mid-tilt, waiting to burgle a tourist stepping out of a cicchetti shop. It was nostalgic and entirely new. It was Venice.

Yet—something tugged at me as I moved deeper into the exhibition.

There’s a pattern in the art world I finally woke up to seven years ago: fame attracts money, money inflates fame, and fame is insatiable. Once someone has enough money to satisfy every ordinary or extraordinary need, they reach for the one thing money can’t buy—immortality. So they attach themselves to whatever is already canonized. None of this is about merit or preserving culture for communities who may not have another advocate; it’s simply how the machinery works. Keep that in mind.

That machinery was visible even here. The museum’s lecture highlighted how Monet reshaped the way modern artists like Spencer Finch think about color and light—but the exhibition itself wasn’t built around Finch or any contemporary works. It was anchored by Monet’s name. Only a handful of the paintings were actually his; the rest were works of Venice, some on loan from private collections, many others withheld. And while I enjoyed hearing from Finch, everyone was here for Monet. That’s the power of fame: it keeps a spotlight burning long after the artist is gone, funded by people who want their names attached to something already immortal. And the deeper you look, the more obvious it becomes that the art world’s hierarchy doesn’t stop at museum walls—it stretches across continents.

Listening to Amy Gross of Save Venice describe the restoration of Tintoretto’s Last Supper, I couldn’t help thinking of the day Notre Dame burned. Within minutes of the news breaking, nearly a billion dollars had been pledged. Some of it came from genuine love—of Paris, of architecture, even of the Catholic Church—but most of it came from clout. The speed of the response made something else brutally clear: there is an enormous amount of spare money in the world, ready to appear instantly, but only for the icons. If Notre Dame revealed how quickly money moves for the infamous, Brazil revealed how quietly the unfamiliar can disappear.

A year earlier, an absolutely catastrophic event occurred at Brazil’s National Museum. Irreplaceable fossils, Indigenous artifacts, ancient human remains, and a scientific archive unmatched in the hemisphere all burned to the ground. The world barely blinked. One fire was treated as a universal tragedy; the other as a regional inconvenience. The difference? In my opinion, it’s simply that Notre Dame was European. Europe’s crises are always treated as global, even when all that was lost was a roof.

The contrast stayed with me—especially as I was being asked to donate to a small, private, immensely wealthy church I had never heard of and that very few people will ever see. It sharpened the question forming in the back of my mind as I returned to the Brooklyn Museum.

As a Brazilian American who literally took the bus to attend this event, the chance to see a European master in my own borough felt like a gift. But it also made me wonder: if the Met burned down and the Brooklyn Museum burned down within a year of each other, would the country respond the same way? Would we only mourn the eight Monet paintings?

I think we know the answer.

New York isn’t the world, but the dynamic is the same: prestige drives urgency. Tourism drives empathy. Fame decides who gets saved.

But what happens to the people who make the work—the ones the world later calls immortal?

In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway writes that the world needs more mystery, more unambitious writers, more beautiful unpublished poems—and then adds a blunt footnote: “There is, of course, the problem of sustenance.” I think about that constantly. Art may thrive on hunger and uncertainty, but artists still have to live. They need rent money. They need time. They need someone to care before the world decides their work is immortal.

Monet understood this too well. Early in his life, he struggled so severely—with debt, with failure, with the relentless pressure to produce—that he attempted suicide. His survival, his eventual home at Giverny, the water lilies, even his time in Venice—none of it would have existed without the people who believed in him before he was “Monet.” His immortality was built on community.

And that’s why the Brooklyn Museum matters so much.

It has always been a public promise—a space built in 1897 to democratize beauty. A place where you can attend a meditation class under soaring ceilings, take a stroller tour, sit in a lecture with strangers, and then step into a room filled with light that traveled across centuries.

So here is the question I carried out of the final gallery:

What could we save if we valued the unfamous with the same urgency we rush to preserve the immortal?

What could we protect if art’s worth weren’t measured by fame, but by need?

And what would culture look like if we invested in artists the way Monet’s friends once invested in him?

Maybe, in the end, that’s the real meditation.

Running through February, be sure to check out the museum’s Monet-themed events, such as yoga and meditation in the morning.