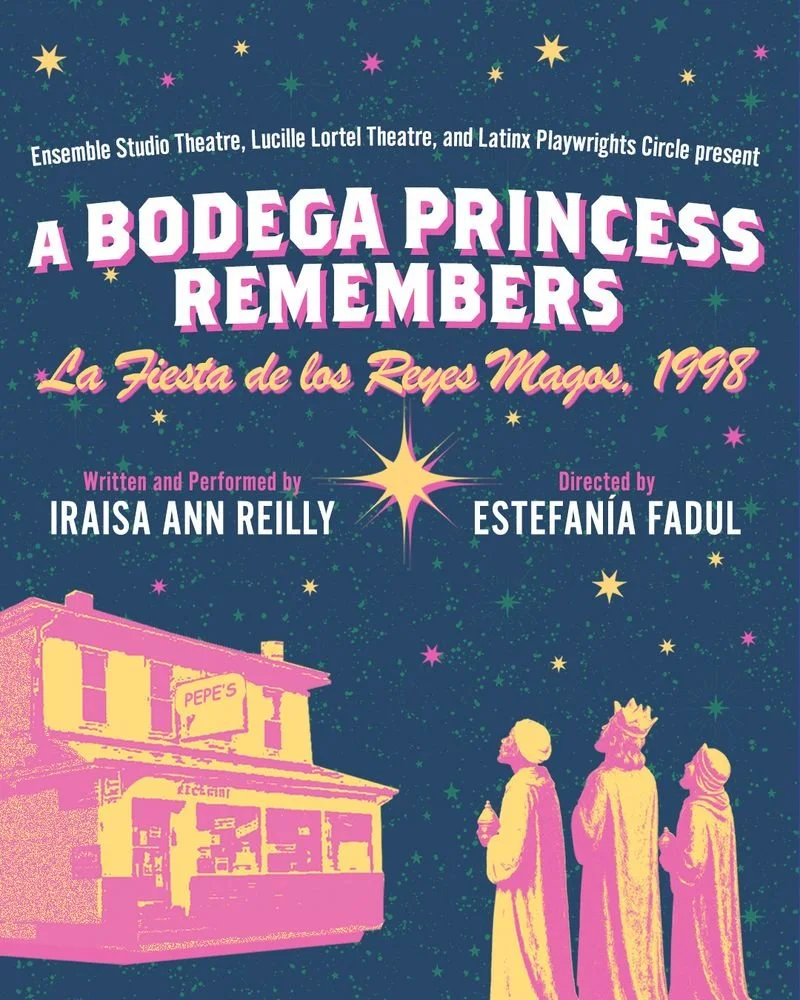

An All American 90’s Holiday Special:A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998

Walking into Ensemble Studio Theatre, the smell of warm, sweet breads and savory, hot fried dough hits me—comforting after coming in from the cold winter winds that funnel down the avenues. Delighted by this welcome, I grab my program and an empanada on a paper plate, then head into the theater.

A TV in the corner plays mid-90s Spanish telenovelas, news snippets, music videos, and commercials. Dionne Farris’s “I Know” plays over the speakers, and slowly everyone in my row starts to quietly sing along to the chorus. It’s the pre-show for Iraisa Ann Reilly’s solo memory play, A Bodega Princess Remembers La Fiesta de los Reyes Magos, 1998. The Off-Broadway run—presented with the Lucille Lortel Theatre and the Latinx Playwrights Circle—continues through December 19th. At about 75–90 minutes with no intermission, it drops you into Reilly’s childhood.

Reilly grew up in Egg Harbor City, New Jersey, where her Cuban-American family ran a bodega. Every January 6th, the local Spanish-speaking community crammed into St. Nicholas School’s basement cafeteria for Los Reyes. Surrounded by folding chairs and card tables covered in plastic tablecloths and tinsel, Reilly—playing her younger self—climbs onto a small wood stage, set directly atop what looks like government-grade gym linoleum, and begins performing the church’s program. Through this moment, we learn how she got there, as she recounts the highs and lows of being the “bodega princess”: her mom starting a Spanish-language choir even after being told there wasn’t room, her grandparents’ escape from Cuba, and her own coming-of-age from ages five through thirteen.

She switches between English and rapid-fire Spanish, but you never feel lost. Her body language fills in any words you miss.

As a Brazilian American who has always hovered between being too much and not enough “Latinx” (partly because Brazil is the largest Latin American country yet speaks a different language, and partly because I wasn’t raised speaking Portuguese), I came in wary. I always sit in these rooms waiting to be reminded that I’m not part of “the group.” Thankfully, Reilly doesn’t shy away from that tension.

One of the most poignant scenes shows young Reilly being pulled from the main school building and sent to the “special class” trailers because she kept using the Spanish word for “olive.” She’s humiliated—not because she doesn’t know English, but because she knows too much Spanish. I thought about the microaggressions that made my own parents decide not to teach us Portuguese. The excuses we made and explanations we offered—“We don’t speak it because it’s more important our mother speaks English well”—or the abuelas who scolded me in Spanish for being “a disgrace to my heritage” for not speaking Spanish or Portuguese.

Hearing Reilly describe her experiences aloud both stung and soothed me. How many of us have had to stand our ground—or surrender parts of ourselves—to fit in? Probably everyone in that room could relate, Latin or not.

And yet, the show never feels heavy. Quite the opposite. Reilly and director Estefanía Fadul layer in 1990s references (Ricky Martin posters, soft-focus telenovelas, Sony boom boxes) and the chaotic joy of a family-run store. You smell the hot food, feel part of the gossip, sense the pride in the Goya cans shelved just right. We’re with Reilly as she reenacts her mother negotiating with an English-language choir director for rehearsal space—and we remember our own teenage mortification at being forced into activities our parents insisted on.

The audience laughs because we’ve all been there. For me, it was the rare bodega in a 50-mile radius that stocked Antárctica Guaraná (iykyk) beside Goya Maracuyá. For my husband—who calls himself “painfully white”—it was being forced to join the band, coming from a long line of proud musicians and composers. The audience follows every beat, with shared body language as its own script and a universally human experience beneath it.

The biggest surprise is how American it all feels. For all its Spanish (and occasional Cuban slang), the heart of the show is universal: a kid trying to figure out who she is; a family determined to hold onto tradition; a community carving out space in a country that keeps asking them to choose. But this country was built on the idea of not choosing—being everything from everywhere at once.

By the time Reilly restages her 1998 Three Kings performance and invites a few audience members to share the spotlight, the room feels like a church basement in any town. You’re reminded that this is America: all the languages, all the foods, all the community basement halls, all the holidays. All of us.

This holiday season, along with the beautiful European holiday shows we often see, I urge you to exercise your patriotism—and take your family to see A Bodega Princess.

Runs Nov 17 – Dec 14, 2025 at Ensemble Studio Theatre, 545 W 52nd Street, Manhattan

Run time: 90 minutes

Tickets: estnyc.org